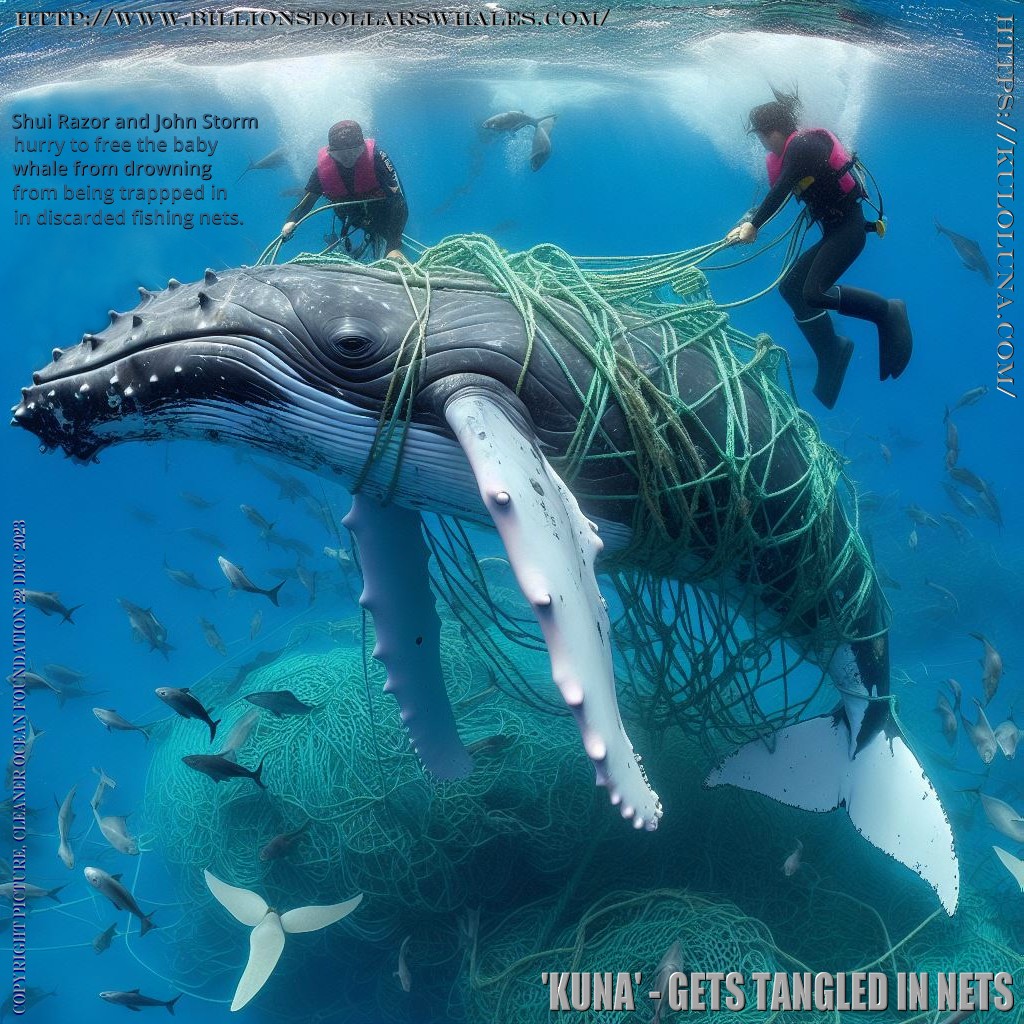

There are some reports and studies about humpback whales being caught up, drowning or otherwise killed in ghost fishing nets or ropes. Ghost fishing is the term used to describe the entanglement or trapping of marine animals by lost or abandoned fishing gear

[9]. Ghost fishing can cause serious injuries, infections, starvation, suffocation, drowning, or predation to the affected animals

[9].

According to web search results, humpback whales are one of the species that are vulnerable to ghost fishing, especially in their migration and breeding grounds

[10] [11]. Some of the examples of humpback whale entanglement by ghost fishing gear are:

- In May 2022, a humpback whale entangled in fishing gear washed up dead close to Scrabster, near Thurso on the north Caithness coast

[10].

- In April 2022, another humpback whale was found to have been entangled in rope for "weeks, if not months" before it drowned off the East Lothian coast near Tyningham

[10].

- In October 2019, a pregnant humpback whale was found dead and tangled in a fishing net in Orkney. The net was jammed in the animal’s baleen, the filter-feeder system inside its mouth

[12].

- In January 2022, a humpback whale was found dead on a beach in Western Australia with a fishing net wrapped around its tail

[13].

These cases illustrate the tragic consequences of ghost fishing for humpback whales and other marine life. Some of the possible solutions to prevent or reduce ghost fishing include:

- Improving the design and durability of fishing gear to minimize the risk of loss or breakage

[9].

- Implementing regulations and incentives to encourage the reporting and retrieval of lost or abandoned fishing gear

[9].

- Supporting the development and use of biodegradable or traceable fishing gear that can degrade or be located over time

[9].

- Raising awareness and education among fishers and consumers about the impacts and solutions of ghost fishing

[9].

- Supporting the research and monitoring of ghost fishing and its effects on marine ecosystems and wildlife

[9].

They

have been carping on about ridding the oceans of ghost fishing gear for

more years than you can shake a stick at. Each year there is a new call

to arms, to action. But, there is no action. The rally cry is nothing

more than a gesture. A hope that someone somewhere will do something.

Instead of the authorities taking direct action to confiscated fishing

boats and fine the perpetrators for causing the unimaginable suffering

the media (thankfully) reports on sporadically.

Then,

it is business as usual. Something like the Climate

COPS, lots of hot air, about hot air, and speeches about good

intentions, then, a massive vacuum of no action - all the while global

warming increases - the world gets hotter. You may see this as a series

of disingenuous and hollow gestures, designed to make the parties look

as though they care for real. All jolly good clean fun for political

careers. And, each nations appears to think that by speaking for

themselves, and despite their past failures, that some fool somewhere

may actually bite the bullet and do something, to offset their

butchering ways. Where doing something, will put a strain on already

strained economies. In a world at war trade wise. The real brake.

Politicians promising growth, in a world where we are already using

roughly 2.4 times the planet's capacity to regenerate. Oh brother!

As

far as we know, the only machine capable of harvesting ghost trawl nets,

was the SeaVax.

Those machines could geo-tag their finds and analyze the plastic. Hence,

there was some possibility of gaining hard evidence to mount

prosecutions.

Whoa!

No wonder the concept was strangled at birth.

The

perpetrators of the crimes against nature, might be brought to account.

Naturally, it was in the interest of fishing nations to make sure that 'system' never saw the light of day. Five years of development and

lobbying later, and the project died from lack of support. The

Foundation was forced to pull the plug, to prevent insolvency. All

because the G20 (all nations) want cheap fish. And no comeback on their

fishing fleets. If net tagging was mandatory, with fines for losing one,

the price of fish would increase. What do you think?

Plastic pollution is a serious threat to marine life and ecosystems. Plastic can affect marine species in various ways, such as:

- Entanglement: Large items of plastic, such as fishing gear, six-pack rings, and plastic bags, can capture and entangle marine mammals, fish, turtles, and birds, and prevent them from escaping, feeding, or moving normally. This can cause injuries, infections, starvation, suffocation, drowning, or predation

[1] [2].

- Ingestion: Small pieces of plastic, such as microplastics and fragments, can be mistaken for food by marine animals, from zooplankton to whales. This can lead to digestive problems, internal injuries, reduced stomach capacity, malnutrition, starvation, or toxic contamination

[1] [2] [3].

- Toxic contamination: Plastic can absorb and release harmful chemicals, such as

persistent organic pollutants (POPs), heavy metals, and endocrine disruptors, into the water or into the tissues of marine organisms. This can affect their growth, development, reproduction, immunity, and behaviour, and potentially cause diseases, mutations, or cancers

[1] [2] [3]. These chemicals can also biomagnify up the food chain, posing risks to human health and food safety

[1] [2].

- Habitat degradation: Plastic can damage or alter the physical structure and function of marine habitats, such as coral reefs, seagrass beds, and mangroves. Plastic can smother, break, or erode these habitats, reducing their biodiversity, productivity, and resilience

[4] [5] [6]. Plastic can also transport invasive species or pathogens across regions, disrupting the ecological balance

[4] [5].

Plastic pollution is a global problem that requires urgent action from all stakeholders, including governments, businesses, consumers, and civil society. Some of the possible solutions include:

- Prevention: Reducing the production and consumption of single-use plastics, promoting circular economy and sustainable design, implementing bans or taxes on plastic products, and raising awareness and education on the impacts of plastic pollution

[4] [5] [6].

- Collection: Improving the waste management and disposal systems, especially in developing countries, to prevent plastic leakage into the environment, and supporting clean-up initiatives and campaigns to remove plastic from the ocean and the coastlines

[4] [5] [6].

- Recycling: Increasing the recycling capacity and efficiency, developing innovative technologies and methods to recycle plastic waste, and creating incentives and markets for recycled plastic products

[4] [5] [6].

- Research: Enhancing the scientific knowledge and understanding of the sources, pathways, fate, and effects of plastic pollution, as well as the potential solutions and alternatives, and supporting the monitoring and assessment of the plastic pollution situation

[4] [5] [6].

UNEP UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME 17 DECEMBER 2018 - HOW TO BANISH THE GHOST OF DEAD FISHING GEAR FROM OUR SEAS

In August, around 300 endangered sea turtles were found dead off the southern coast of Mexico, trapped in what was believed to be an abandoned fishing net. The deaths of the olive ridley

turtles dramatically underscored the dangers posed by lost or discarded fishing equipment or so-called ghost gear.

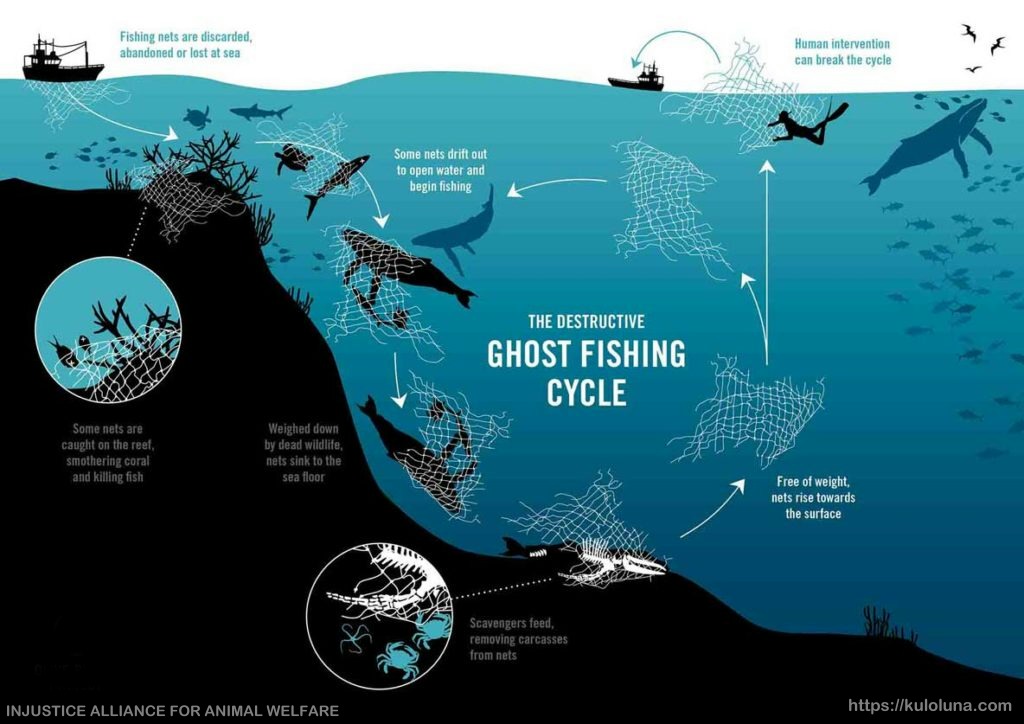

The figures are staggering: each year more than 100,000 whales, dolphins,

seals and turtles get caught in abandoned or lost fishing nets, long lines, fish traps and lobster pots. Some of the abandoned nets can be as big as football pitches, and this plastic-based ghost gear can take up to 600 years to break down, shedding microplastics as it degrades.

Seabirds gather pieces of netting to make their nests and can then get entangled. Ghost gear also threatens shallow coral reefs and damages fisheries by killing seafood that would otherwise form part of the global catch, costing

millions of dollars in losses.

While public awareness of marine plastic pollution has fuelled a global movement to eliminate unnecessary single-use plastics from our daily lives, the damage caused by ghost gear is less well known, partly because the deadly consequences play out on the high seas, far from human scrutiny.

It is estimated that between 600,000–800,000 metric tonnes of ghost gear enters the ocean each year, with some of it lost during storms and some deliberately dumped. Nick Mallos, Director of the Trash Free Seas Program at Ocean Conservancy, says this is likely a conservative estimate.

“Ghost gear is the most deadly form of marine litter out there. It is a very serious form of debris that has a very real impact,” he said.

Ocean Conservancy will assume the leadership of the Global Ghost Gear Initiative in January, taking over from World Animal Protection. Mallos says there is a strong impetus across the sector to prevent the loss of more gear and collect and recycle what is already in our oceans.

OCTOBER

2019 - In Scotland, the Scottish Marine Animal Strandings Scheme (Smass), which investigates marine animal deaths, recorded 12 entanglement cases in 2019.

They included a pregnant Minke whale found dead and tangled in a fishing net in Orkney in October. The net was jammed in the animal's baleen, the filter-feeder system inside its mouth.

In May, a humpback whale entangled in fishing gear washed up dead close to Scrabster, near Thurso on the north Caithness coast.

The previous month, another humpback whale was found to have been entangled in rope for "weeks, if not months" before it drowned off the East Lothian coast near Tyningham.

A sperm whale that died after stranding on the Isle of Harris in November had a 100kg "litter ball" in its stomach.

Fishing nets, rope, packing straps, bags and plastic cups were among the items discovered in a compacted mass during an investigation by Smass.

Seals have also been caught up in nets and ropes, though there have been successful rescues of these animals, including the saving of a five-week-old grey seal pup entangled in a plastic net on Lewis.

A hotline run by British Divers Marine Life Rescue (BDMLR) has received 47 reports of entangled seals this year in Britain. Some of the animals were lucky and were rescued, or managed to free themselves.

In 2017, stags on the Isle of Rum were found with fishing gear caught in their antlers. Two of the animals died after becoming snarled up together in discarded fishing rope, while another stag was photographed with an orange buoy and rope balled up in its antlers.

Launched in 2015, the Global Ghost Gear Initiative brings together governments, private sector corporations, the fishing industry, non-governmental organizations and academia to tackle the problem of lost and abandoned fishing gear. UN Environment, which launched its Clean Seas campaign in 2017 to encourage governments, businesses and people to act against plastic pollution, is also part of the Global Ghost Gear Initiative.

For Mallos, the buy-in from all those concerned has been impressive, but the momentum must be maintained to protect marine wildlife and coastal communities.

“Working with fishers and working with local organizations to create collaborative cross-sector partnerships to remove gear, particularly from ecologically sensitive habitats, is an important workstream that will continue. Another piece that is critically important, and has really taken off this year, is looking at ways to continue scaling the Best Practice Framework for the Management of Fishing Gear globally,” Mallos said.

The Framework recommends practical solutions to prevent and mitigate the impacts of lost gear across the entire seafood supply chain from gear manufacturers to port operators. It provides case studies on how changes have been achieved in net recycling programmes, derelict gear retrieval and fishing management policies.

“It is not just an academic or theoretical exercise. We are seeing these best practices implemented into supply chains with some of the corporations with whom we work. The Global Ghost Gear Initiative is in the process of working with different certification bodies to see how we can incorporate the best practices for gear management into these various certification schemes,” Mallos said.

Some of the solutions being considered include marking fishing gear at the manufacturing stage, promoting the development of biodegradable fishing pots, and encouraging innovative designs to make it easier to recycle the plastics used by the

fishing industry. Manufacturers could also provide incentives and facilities for fishers to return their gear at the end of its life. The key is to integrate fishing gear fully into a

circular

economy.

However, illegal fishing remains a block to progress. Sometimes illegal fishing boats will dump their equipment to evade detection, legal action or fines.

“Just like all aspects of marine debris, whether it is consumer plastics or fishing gear, there is no silver bullet solution,” said Mallos. “We are not going to tackle all sources and origins with a single approach. Even with the best practices being put forth, there is going to be that, for the most part, uncontrollable aspect of illegal fishing.”

Alongside efforts to prevent the loss of gear in the first place, the Global Ghost Gear Initiative is working with partners to clear the nets, hooks, lines and traps that are already drifting silently through our seas and recycle them to make new products.

Danish company Plastix Global recycles ghost gear collected from Global Ghost Gear Initiative projects in Britain and Alaska, turning it into plastic pellets, plastic tokens for festivals or supermarkets, and local crafts. In Chile, the Net Positiva project provides fishers with disposal points for used gear and then recycles it into sunglasses, frisbees, chairs and skateboard decks.

Across the Mediterranean, Adriatic and North Seas, Healthy Seas collects ghost gear and provides it to producer Aquafil, which makes Econyl, a nylon yarn, used to create sportswear, swimwear, underwear and carpets. Econyl’s creators say it is the same as brand new nylon and can be recycled, recreated and remoulded again and again.

Pioneering solutions like this will be front-and-centre at the fourth UN Environment Assembly when it meets next March to tackle some of the world’s toughest challenges. The meeting’s motto is to think beyond prevailing patterns and live within sustainable limits.

Many ghost gear recycling projects directly involve fishers and coastal communities, who, in the past, were often considered part of the problem. Today, Mallos said, there is a recognition that ghost gear is a “lose-lose” situation for everyone.

“When there is a large amount of ghost gear out there, it affects fishers’ bottom lines, it affects the future sustainability of otherwise harvestable catch, and often it prevents them from spending more time on the water,” he said.

The Global Ghost Gear Initiative hopes that by 2030 the global tonnage of gear that is lost in the ocean annually will be equal to or smaller than the amount of gear that is recovered, recycled and re-used.

“While the threat from fishing gear is very different from that of consumer plastics, when we think about what is the most appropriate and effective mechanism to stop impact in the ocean, it’s exactly the same: let’s stop it at its source and prevent it from getting lost in the first place,” Mallos said.

ABANDONED, LOST & DISCARDED FISHING GEAR (ALDFG)

While there has been some progress and willingness to address the issue of ocean plastic, thus far, Abandoned, Lost and Discarded Fishing Gear (ALDFG) has not been explicitly mentioned in the international legally binding instrument on plastics.

ALDFG, also known as ghost gear, is both the most harmful form of marine debris and one of the most significant contributors to ocean plastics. A single abandoned net is estimated to kill an average of 500,000 marine

invertebrates (think crabs and shrimp), 1,700 fish and four seabirds. Some estimates show that an as much as 30% decline in fish stocks can be attributed to ghost gear.

Furthermore, scientists estimate that up to 70% of all floating macroplastics in ocean gyres by weight are from ALDFG. When swallowed, ocean plastics have been shown to block the digestive tracks and eventually kill marine animals of all sizes. In May 2020, after performing a necropsy on a 47-foot-long beached sperm whale, scientists discovered that its stomach was filled with a mass of fishing line, fishing nets and other plastics which prevented it from absorbing nutrients.

The science is clear - ghost gear, a major source of ocean plastics, must be addressed in order to protect marine life and environments, and the fisher and coastal communities that rely on it for their livelihoods. Thus, if we want to collectively tackle plastic pollution and its impact on the environment, a holistic strategy must include recognition of the threat of ghost gear and binding measures to prevent and mitigate its impacts on an international level.

More than 12 million tons of plastic end up in our seas every year. Plastic pollution plagues every corner of the ocean and despite growing awareness, the problem is only getting worse.

Fishing gear accounts for roughly 10% of that debris: between 500,000 to 1 million tons of fishing gear are discarded or lost in the ocean every year. Discarded nets, lines, and ropes now make up about 46% of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

Ghost fishing gear is the deadliest form of marine plastic as it unselectively catches wildlife, entangling marine mammals, seabirds, sea turtles, and sharks, subjecting them to a slow and painful death through exhaustion and suffocation. Ghost fishing gear also damages critical marine habitats such as coral reefs. Additionally, it’s responsible for the loss of commercially valuable fish stocks, undermining both the overall sustainability of fisheries as well as the people who depend on fish for food and livelihoods.

EARTH.ORG 23 NOVEMBER 2020 - UP TO A MILLION TONS OF GHOST FISHING NETS ENTER THE OCEANS EACH YEAR - STUDY

Recent figures from the WWF indicate that between 500 000 and one million tons of ghost fishing equipment are abandoned in the ocean each year. Ghost nets are lost, abandoned or discarded fishing gear left by fishermen. The proliferation of discarded ghost nets is a major issue for marine life and sea habitats, as well as the commercial fishing industry and marine vessels themselves. It is estimated that ghost nets make up 46% of the

Great Pacific Garbage Patch (now 1.6 million square km in size, three times that of France) and up to 10% of all marine litter.

Ghost nets are made from a range of synthetic fibers, nylon and other plastic compounds and are able to travel vast distances once lost or abandoned. The most common type of ghost net is called a gillnet (also referred to as a driftnet) which, if exceeding 2.5km in length, have been banned within international waters by the UN since 1992. Gillnets are used on top of the water’s surface as well as on the seabed, acting like a wall in which fish and other marine life become quickly entangled. There are also pots and other box-like traps. Fish Aggregating Devices (FADs) are typically bamboo netting with buoys attached, and are used beneath a fishing boat to trap extra catch. Purse seine netting, named for its purse-like structure, works to envelop schools of fish, pulled to the surface at the right moment. Trawling involves large volumes of netting being pulled along the back of a heavy boat. Due to the nature of this practice, netting can become easily caught at the bottom of the ocean. Fish cages, wiring and hooks are also classified as ghost fishing equipment.

Ghost nets are a threat to a multitude of ocean species, big and small: Ghost nets don’t only catch fish; they also entangle sea turtles, dolphins, porpoises, birds, sharks and seals. These animals swim into nets, often unable to detect them, and either sustain injuries or are drowned or suffocated. In 2018, it was reported that up to 650 000 marine animals are killed by ghost nets every year. If the animal is lucky enough to escape, it may still die from its injuries. Often these tragic circumstances cause a long, painful death. If the ghost net is caught on the seabed, smaller ocean creatures begin feeding on the dead catch in the nets, reducing its weight and allowing the netting to float up to the surface again. This in turn creates a destructive cycle.

Figures indicate that over 40 000 tons of gillnets are abandoned every year in South Korean waters (where the netting is particularly popular) each year. In the North-East Atlantic, 25 000 ghost nets are discarded each year – totalling up to 1 250km in length. Between 2014 and 2015, volunteers retrieved marked ghost nets that travelled 4 700km from Maine, USA to the Cornish coast in England, totalling 51 tonnes of netting. 7 000km worth of gillnets are lost in the

Atlantic Ocean annually, while in the United Arab Emirates, 260 000 traps are lost yearly and 250 000 in the

Gulf of

Mexico. A 12-month study in Thailand waters showed that 96% of tangled animals were non-targets for fishermen. Finally, between 2004 and 2015, 13 000 ghost nets were removed from the northern coast of Australia.

It takes approximately 600-800 years on average for ghost fishing nets to naturally decompose.

Seals and sea lions are particularly vulnerable, according to the WWF report, finding that 1 500 Australian sea lions die annually due to entanglement; 53% of these entanglements between 1997 and 2002 involved pups. In 2018, more than 300 300 dead olive ridley sea turtles were spotted off the coast of Mexico. It was determined that they died from hooks and nets. Further, more than 80% of Indian Ocean dolphins have been killed from gillnets, classified as ‘by-catch’ while fishermen were fishing for tuna. Also, the Vaquita (the most critically endangered ocean species) is facing imminent extinction due to illegal fishing in the Sea of Cortez, the one place where vaquitas are found. However, they are collateral in the search for the Totoaba fish, highly desired for its medicinal properties. As of March 2020, there are only ten remaining Vaquita in the ocean.

APRIL

2019 - A humpback whale was entangled in rope for "weeks, if not months" before it drowned off the coast of East Lothian, a post-mortem examination has found.

The young male, which was about nine metres long (30ft), was found at John Muir Country Park, near Tyningham.

Experts said the marine mammal had become very weak and had the most parasites they had ever seen.

The whale was towed out to sea and moved to another beach for the five-hour necropsy on Wednesday.

Dr Andrew Brownlow, veterinary pathologist for the Scottish Marine Animal Stranding Scheme, told the BBC Scotland news website he had found nothing in the whale's stomach.

He said: "This was an entanglement case and from the tissue lesions it had been like this for weeks, if not months.

"It stops the animal from being able to feed properly or exhibit normal behaviour, which weakens the animal and then it drowns.

"It's a real eye opener for us on the effect we can have on animals."

He added: "Its lesions were very chronic and its parasite burden was the most I have ever seen in an animal of this size.

"It had become weak because it could not feed which, in turn, meant its immune system weakened, which meant its parasite burden increased.

"So the poor animal was fighting the ropes and a heavy burden of parasites."

He said he was pleased at least to find no plastic in the whale's stomach.

Dr Brownlow said fishermen's ropes were often longer than the distance from the surface of the sea to the bottom so they formed coils, which was a trap for anything that swam through it.

He added: "In evolutionary terms a whale has learned to spin around to avoid an attachment but this strategy is the worst thing it could do when it's entangled as it makes the situation worse.

"It then has caught something else on the ropes around it which has made it a higher weight and it's actually drowned. It was pretty horrific."

Humpback whales breed in warmer waters in the Azores before moving to more northern waters to take advantage of the food stocks during the summer months.

In October last year, a pregnant minke whale was found beached on the coast of Scotland with ghost netting knotted in its mouth. Representatives from Scottish Marine Animal Stranding Scheme said, “It looked like it had become recently entangled in a section of discarded or lost fishing net – this had become jammed in the baleen and then dragged behind the animal. This would have hugely impaired the animal from feeding or swimming normally, and likely led to an exhausting last few hours of life. Based on the flank bruising and lungs, it appears this creature live stranded and drowned in the surfline.”

Abandoned ghost nets are also doing considerable damage to marine habitats. This is because the netting has a smothering effect on reefs and consequently attracts invasive species, disease and parasites to

coral

reefs, causing long-term damage to the ecosystem. Damage to habitats can also occur when trawling and

lobster pots (netted cages designed to capture a range of crustaceans) destroy fragile coral during strong currents and storms.

The benthos – ocean bottom regions - are also susceptible to the impacts from discarded fishing gear and ghost fishing. Discarded fishing gear, especially trap gear, sinks to the bottom where it can smother organisms that live on top of and just below the sediments, like seagrasses,

crabs, and worms. These harmful practices are counterproductive to fishermen, who will ultimately suffer the consequences of destroying marine ecosystems as their catches will be affected. It is estimated that 53% of the world’s fisheries are fully exploited, while a further 32% are considered to be overexploited or recovering from overexploitation. Ghost fishing nets are left in the sea for a variety of reasons. Gear may be abandoned when fishermen cannot retrieve the net due to it snagging on rocks and coral on the seabed. Some fishing vessels cannot afford to retrieve stuck gear. Fishing nets are considered lost when marker buoys become detached or if heavy tides remove netting from its original location of deployment. Retrieval becomes especially difficult if the vessel does not use GPS technology. Sometimes ghost nets are abandoned deliberately due to poor on-shore facilitation for disposal as well as high disposal costs. Additionally, if an illegal fishing vessel is in danger of being caught, nets may be cut off or thrown overboard.

There are a great number of solutions and technological measures that have been implemented to help retrieve ghost nets – if used more broadly with government support, the clean-up process could be more efficient and widespread. Producing nets with biodegradable components could shorten the time that abandoned gear is left intact in the ocean. Project NetTag is working on a special underwater acoustic transponder for fishermen to secure to their gear. About the size of a matchbox, these transponders have batteries similar to smartphones, but use circuitry which requires very low power, which means they can operate for many months attached to a net. Another

European project called MarGnet has been researching the effectiveness of a sonar device which is attached to the seabed to decipher pollution hot-spots through generating an 360 degree underwater map which is then investigated by diving teams. Underwater drones such as Deep Trekker’s Remote Operated Vehicles (ROVs) are able to operate in extreme weather conditions and are a useful tool in locating ghost nets. In 2015, a WWF-led search along the

Baltic Sea resulted in 268 tons of ghost fishing gear being removed from the ocean. There are plenty of other examples of grassroot clean-up of missions.

WHAT CAN BE DONE?

Governments across the world should do more to remove ghost nets and clamp down on illegal fishing. World Animal Protection has formed a Global Ghost Gear Initiative that calls for an alliance of governments and organisations to share data, resources and education on the issue as well as coordinate search efforts. The

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) underpin the rules and legalities of human activity at sea, but WWF says that more action must be taken to apply these regulations. Article 194 of the convention provides for state regulation of fishing gear by providing the licensing of fishing equipment used in waters under national jurisdiction. However, implementation and enforcement should be strengthened at the global, regional and national levels, including through the adoption of adequate implementing legislation.

In 2009, the European Community Council Regulation enforced a law stating that fishermen are obligated to retrieve and report lost netting. However, Greek fisherman Vannis Athinaios has witnessed this law being ignored: “The law is not enforced. Most of us have equipment like GPS and plotters. Big boats have advanced equipment and crews of divers to track lost gear down, but they don’t do it because they can make €6,000, the cost say, of a lost net on any given day.” In 2008, The FAO Committee on Fisheries set guidelines for marking fishing gear, however they are voluntary. Elizabeth Hogan of Oceans and Wildlife with World Animal Protection says that governments should take the matter more seriously, “This would not only result in loss prevention by responsible

fisheries, it would also help stop

illegal fishing (IUU), which accounts for intentionally discarded gear (typically abandoned at sea to avoid detection). IUU fishing costs the global economy US$20 billion annually. Marked gear would help authorities track illegal fishing activity and bring criminals to justice.”

Overall, more awareness and education needs to be provided to better communicate the pervasiveness, danger and durability of ghost fishing equipment within our oceans. With ghost nets dubbed the ‘silent killers’ of the sea, the problem can only be addressed if governments come together on a world-wide level and work collectively to reduce unnecessary marine-life deaths. As of now, 16 governments have joined forces to achieve the goals of the Global Ghost Gear Initiative. If more governments make a commitment to carefully enforce strict rules and regulations to rid the oceans of this marine litter, this would be a great step in helping to establish much healthier oceans and safer marine life.

https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/how-banish-ghosts-dead-fishing-gear-our-seas

https://sdgs.un.org/statements/global-ghost-gear-initiative-15704

https://earth.org/up-to-a-million-tons-of-ghost-fishing-nets-enter-the-oceans-each-year-study/

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-highlands-islands-50510666

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-edinburgh-east-fife-48051954

[1]

https://news.fullerton.edu/2022/11/new-study-reveals-alarming-amount-of-microplastics-ingested-by-baleen-whales-off-californias-coast/

[2] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/nov/01/whales-ingest-millions-of-microplastic-particles-a-day-study-finds

[3] https://www.plasticsoupfoundation.org/en/2021/12/surprising-findings-from-new-research-into-microplastics-in-whales/

[4]

https://www.fauna-flora.org/explained/how-does-plastic-pollution-affect-marine-life/

[5] https://www.iucn.org/resources/issues-brief/marine-plastic-pollution

[6] https://www.unep.org/topics/ocean-seas-and-coasts/ecosystem-degradation-pollution/plastic-pollution-and-marine-litter-0

[7] https://www.wwf.org.uk/updates/how-does-plastic-end-ocean

[8] https://www.iucn.org/story/202207/plastic-pollution-crisis

[9]

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-highlands-islands-50510666

[10] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-55987350

[11] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-61991111

[12] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-north-east-orkney-shetland-49971798

[13] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/jan/17/entangled-humpback-whales-sad-fate-has-researchers-calling-for-action-on-fishing-nets

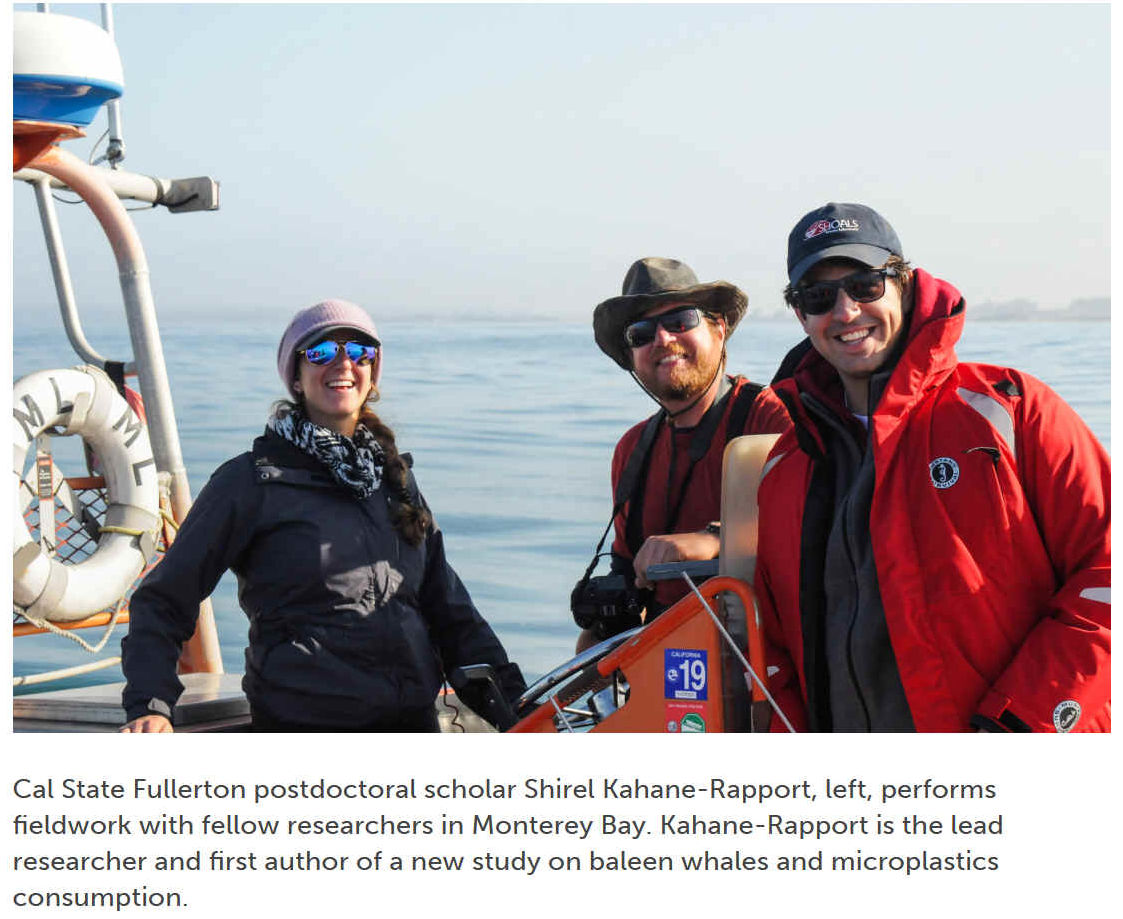

[1] https://news.fullerton.edu/2022/11/new-study-reveals-alarming-amount-of-microplastics-ingested-by-baleen-whales-off-californias-coast/

[2] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/nov/01/whales-ingest-millions-of-microplastic-particles-a-day-study-finds

[3] https://www.plasticsoupfoundation.org/en/2021/12/surprising-findings-from-new-research-into-microplastics-in-whales/

[4]

https://www.fauna-flora.org/explained/how-does-plastic-pollution-affect-marine-life/

[5] https://www.iucn.org/resources/issues-brief/marine-plastic-pollution

[6] https://www.unep.org/topics/ocean-seas-and-coasts/ecosystem-degradation-pollution/plastic-pollution-and-marine-litter-0

[7] https://www.wwf.org.uk/updates/how-does-plastic-end-ocean

[8] https://www.iucn.org/story/202207/plastic-pollution-crisis

[9]

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-highlands-islands-50510666

[10] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-55987350

[11] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-61991111

[12] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-north-east-orkney-shetland-49971798

[13] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/jan/17/entangled-humpback-whales-sad-fate-has-researchers-calling-for-action-on-fishing-nets

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-highlands-islands-50510666

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-edinburgh-east-fife-48051954

https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/how-banish-ghosts-dead-fishing-gear-our-seas

https://sdgs.un.org/statements/global-ghost-gear-initiative-15704

https://earth.org/up-to-a-million-tons-of-ghost-fishing-nets-enter-the-oceans-each-year-study/

ABS

- BIOMAGNIFICATION

- CANCER

- CARRIER

BAGS - COTTON

BUDS

DDT

- FISHING

NETS - HEAVY

METALS - MARINE

LITTER

MICROBEADS

- MICRO

PLASTICS - NYLON

- OCEAN

GYRES

OCEAN

WASTE - PACKAGING

- PCBS

- PET

- PLASTIC

PLASTICS

- POLYCARBONATE

- POLYSTYRENE

POLYPROPYLENE

-

POLYTHENE - POPS

PVC

- SHOES

- SINGLE

USE - SOUP

STRAWS

- WATER

Please use our

A-Z INDEX to

navigate this site