|

BRUCE - THE SHARK

|

|||||

|

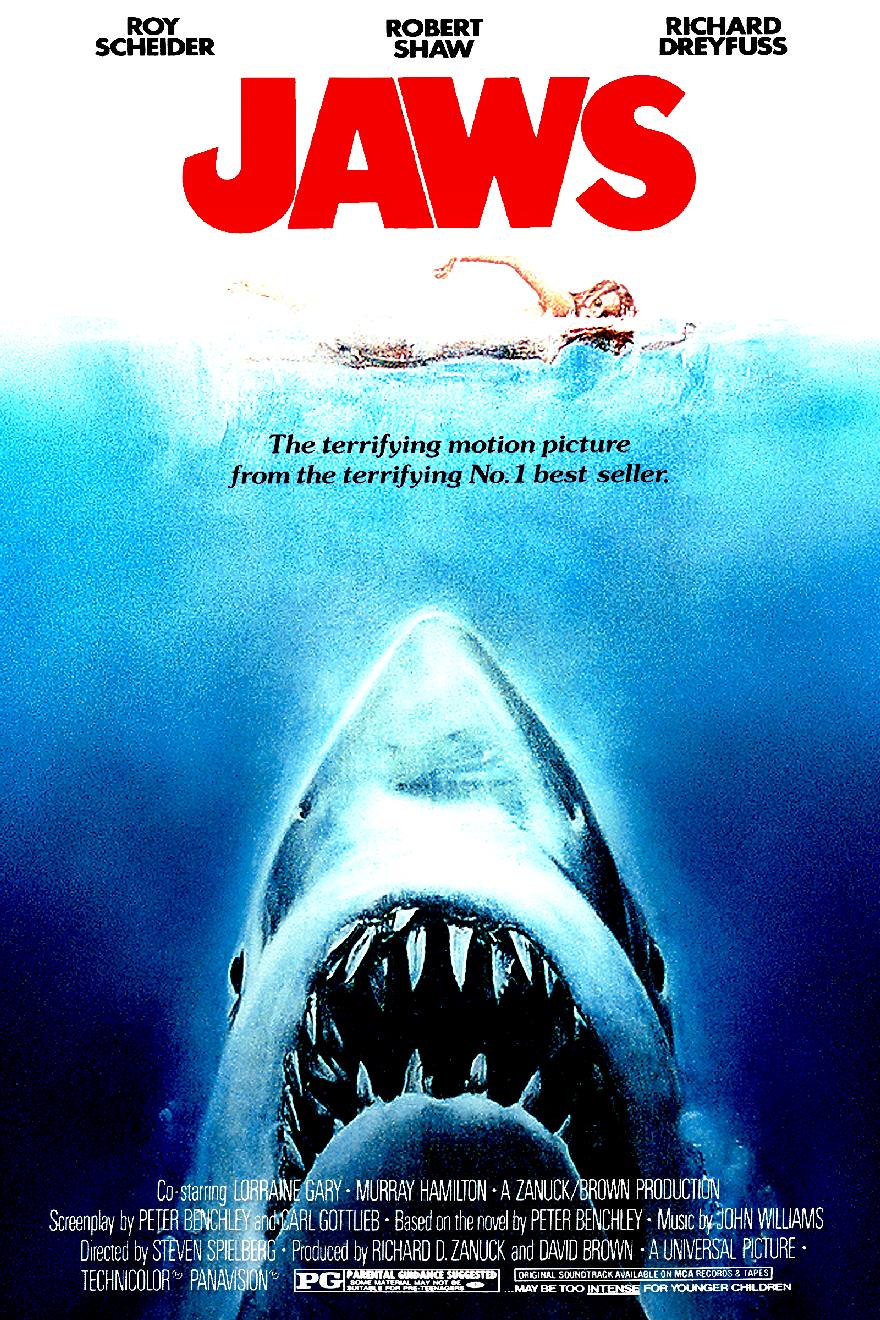

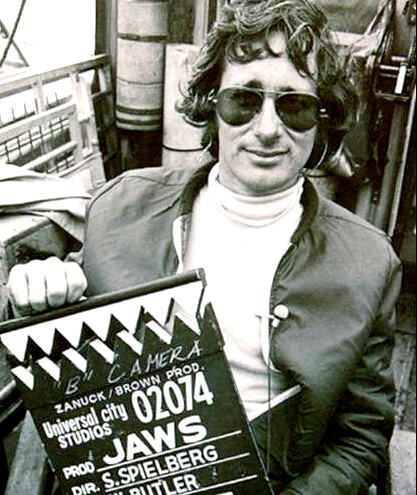

POSTER ART - The developers spent around six months working on the poster art for Jaws, more time than it took Peter Benchley to dream up the plot. Steven Spielberg cut his teeth on the meaty role Jaws presented, directing a film using a giant rubber shark model, sometimes on submerged rails, that was camera shy. Oddly enough, having to resort to Alfred Hitchcock like suspense building, in not showing 'Bruce,' as the flawed animatronic became known, the lack of props actually helped to make the film a success.

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

Anyone who has a passing interest in the Jaws movie knows that the animatronic shark kept breaking down. This turned out to be a blessing in disguise, because

Steven Spielberg had to add more character development and depth to the script to build tension. Not though a great beginning for marine animatronics.

|

|||||

|

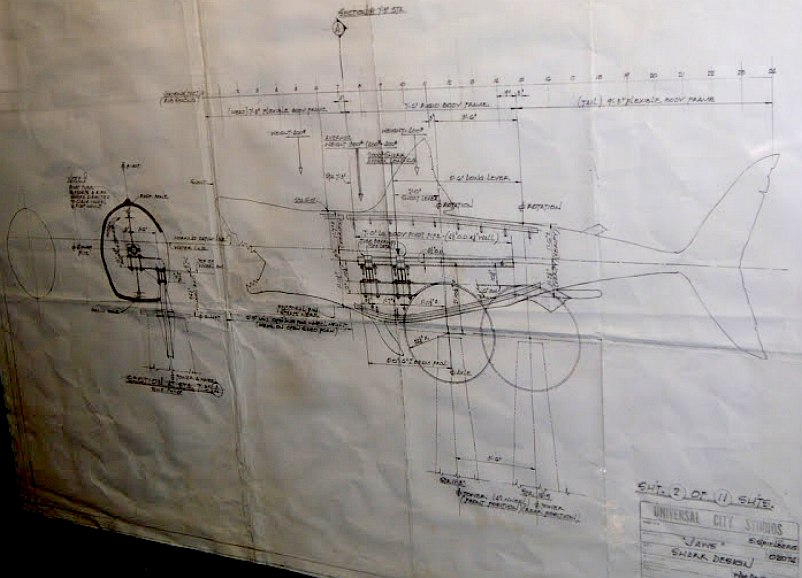

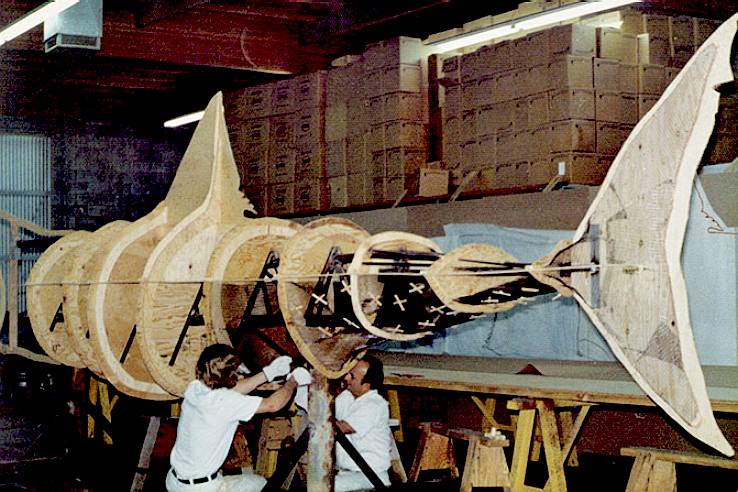

BRUCE - was built with plywood formers as you can see, mated to steel frames wherever there is a hinge for movement. We are not sure if any of the Jaws sharks were designed to emulate a real swimming stroke authentically, but if we get to make our shark, we'll be sure to study a real fish and replicate that movement as far as practical.

LAUNCH PLATFORM - Not exactly elegant, but this is the floating rig or raft from which 'Bruce,' one of the animatronic sharks used to make the Jaws movie was launched and recovered. Obviously they did not care about longevity, using untreated softwood for the frames. We are taking a different approach.

KONTIKI - One of the most famous rafts in history was that used by Thor Heyerdahl for his Kontiki expedition in 1947. Thor was born in 1914 and celebrated his 100th birthday on the 6th of October 2014. The Kontiki raft covered 4,300 nautical miles in 101 days at an average speed of 42.5 miles per day.

WALT CONTI - Any filmmaker tasked with creating realistic marine predators has to measure up to a larger-than-life specter lurking just beneath the waves: Steven Spielberg's iconic animatronic shark, Jaws. Walt Conti—whose company Edge Innovations has created robot creatures for Free Willy, Deep Blue Sea and now Shark Night 3D, out Sept. 2—is used to hearing the comparisons. But Spielberg's 1970s icon can't compare to the technology behind today's Hollywood predators. "People bring up Jaws all the time," he says. "It's like comparing a Model T to a Ferrari. They both have four wheels and engines, but the animatronics we create today are highly tuned machines. From an engineering standpoint, they're a completely different level of power."

MEMORIES - Most of us remember this shark. It thrilled audiences back in 1970s but the movie was almost a flop without a sound track, and the unreliability of several left and right models nearly floored Spielberg's career before it began. Thankfully, Steven proved to be more resilient and simply adapted his script in the face of mounting technical and financial issues - the mark of an adaptable director and true producer.

|

|||||

|

Please use our A-Z INDEX to navigate this site or return HOME

This website is Copyright © 2021 Cleaner Ocean Foundation Ltd and Jameson Hunter Ltd Kulo Luna™ is a registered trade mark with international application(s) pending.

|